Rendering HTML with JavaScript is different than rendering HTML that's sent by the server—and that can affect performance. Learn the difference in this guide, and what you can do to preserve your website's rendering performance—especially where interactions are concerned.

Parsing and rendering of HTML is something that browsers do very well by default for websites that use the browser's built-in navigation logic—sometimes called "traditional page loads" or "hard navigations". Such websites are sometimes called multi-page applications (MPAs).

However, developers may work around browser defaults to suit their application needs. This is certainly the case for websites using the single page application (SPA) pattern, which dynamically creates large parts of the HTML/DOM on the client with JavaScript. Client-side rendering is the name for this design pattern, and it can have effects on your website's Interaction to Next Paint (INP) if the work involved is excessive.

This guide will help you weigh the difference between using HTML sent by the server to the browser versus creating it on the client with JavaScript, and how the latter can result in high interaction latency at crucial moments.

How the browser renders HTML provided by the server

The navigation pattern used in traditional page loads involves receiving HTML from the server on every navigation. If you enter a URL in the address bar of your browser or click on a link in an MPA, the following series of events occurs:

- The browser sends a navigation request for the URL provided.

- The server responds with HTML in chunks.

The last step of these is key. It's also one of the most fundamental performance optimizations in the server/browser exchange, and is known as streaming. If the server can begin sending HTML as soon as possible, and the browser doesn't wait for the entire response to arrive, the browser can process HTML in chunks as it arrives.

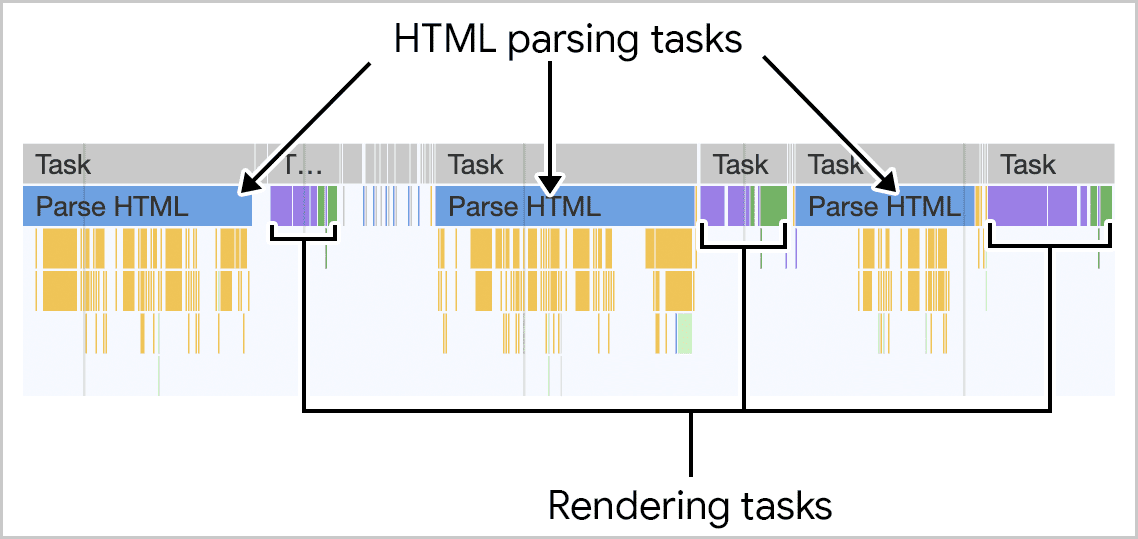

Like most things that happen in the browser, parsing HTML occurs within tasks. When HTML is streamed from the server to the browser, the browser optimizes parsing of that HTML by doing so a bit at a time as bits of that stream arrive in chunks. The consequence is that the browser yields to the main thread periodically after processing each chunk, which avoids long tasks. This means that other work can occur while HTML is being parsed, including the incremental rendering work necessary to present a page to the user, as well as processing user interactions that may occur during the page's crucial startup period. This approach translates to a better Interaction to Next Paint (INP) score for the page.

The takeaway? When you stream HTML from the server, you get incremental parsing and rendering of HTML and automatic yielding to the main thread for free. You don't get that with client-side rendering.

How the browser renders HTML provided by JavaScript

While every navigation request to a page requires some amount of HTML to be provided by the server, some websites will use the SPA pattern. This approach often involves a minimal initial payload of HTML is provided by the server, but then the client will populate the main content area of a page with HTML assembled from data fetched from the server. Subsequent navigations—sometimes referred to as "soft navigations" in this case—are handled entirely by JavaScript to populate the page with new HTML.

Client-side rendering may also occur in non-SPAs in more limited cases where HTML is dynamically added to the DOM through JavaScript.

There are a few common ways of creating HTML or adding to the DOM through JavaScript:

- The

innerHTMLproperty allows you to set the content on an existing element via a string, which the browser parses into DOM. - The

document.createElementmethod allows you to create new elements to be added to the DOM without using any browser HTML parsing. - The

document.writemethod allows you to write HTML to the document (and the browser parses it, just like in approach #1). Due to a number of reasons, however, usage ofdocument.writeis strongly discouraged.

The consequences of creating HTML/DOM through client-side JavaScript can be significant:

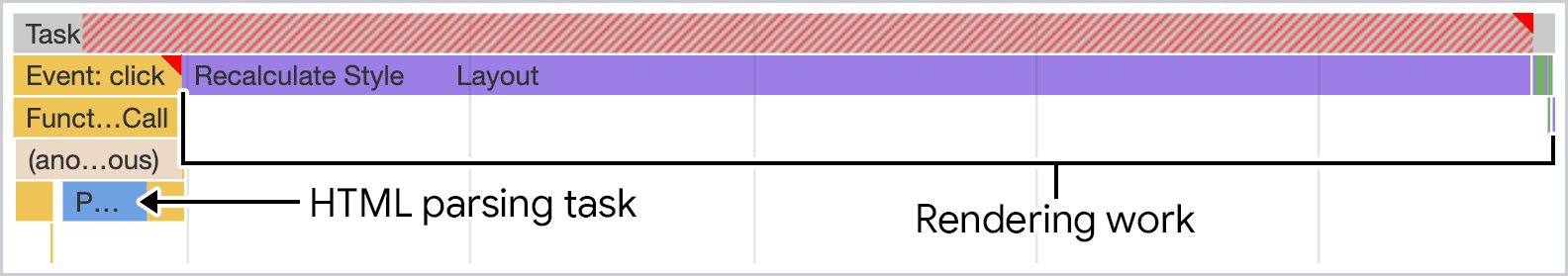

- Unlike HTML streamed by the server in response to a navigation request, JavaScript tasks on the client are not automatically chunked up, which may result in long tasks that block the main thread. This means that your page's INP can be negatively affected if you're creating too much HTML/DOM at a time on the client.

- If HTML is created on the client during startup, resources referenced within it will not be discovered by the browser preload scanner. This will certainly have a negative effect on a page's Largest Contentful Paint (LCP). While this is not a runtime performance issue (instead it's an issue of network delay in fetching important resources), you don't want your website's LCP to be affected by sidestepping this fundamental browser performance optimization.

What you can do about the performance impact of client-side rendering

If your website depends heavily on client-side rendering and you've observed poor INP values in your field data, you might be wondering if client-side rendering has anything to do with the problem. For example, if your website is an SPA, your field data may reveal interactions responsible for considerable rendering work.

Whatever the cause, here are some potential causes you can explore to help get things back on track.

Provide as much HTML from the server as possible

As mentioned earlier, the browser handles HTML from the server in a very performant way by default. It will break up parsing and rendering of HTML in a way that avoids long tasks, and optimizes the amount of total main thread time. This leads to a lower Total Blocking Time (TBT), and TBT is strongly correlated with INP.

You may be relying on a frontend framework to build your website. If so, you'll want to make sure you're rendering component HTML on the server. This will limit the amount of initial client-side rendering your website will require, and should result in a better experience.

- For React, you'll want to make use of the Server DOM API to render HTML on the server. But be aware: the traditional method of server-side rendering uses a synchronous approach, which can lead to a longer Time to First Byte (TTFB), as well as subsequent metrics such as First Contentful Paint (FCP) and LCP. Where possible, make sure you're using the streaming APIs for Node.js or other JavaScript runtimes so that the server can begin streaming HTML to the browser as soon as possible. Next.js—a React-based framework—provides many best practices by default. In addition to automatically rendering HTML on the server, it can also statically generate HTML for pages that don't change based on user context (such as authentication).

- Vue also performs client-side rendering by default. However, like React, Vue can also render your component HTML on the server. Either take advantage of these server-side APIs where possible, or consider a higher-level abstraction for your Vue project to make the best practices easier to implement.

- Svelte renders HTML on the server by default—although if your component code needs access to browser-exclusive namespaces (

window, for example), you may not be able to render that component's HTML on the server. Explore alternative approaches wherever possible so that you're not causing unnecessary client-side rendering. SvelteKit—which is to Svelte as Next.js is to React—embeds many best practices into your Svelte projects as possible, so you can avoid potential pitfalls in projects that use Svelte alone.

Limit the amount of DOM nodes created on the client

When DOMs are large, the amount of processing time required to render them tends to increase. Whether your website is a full-fledged SPA, or is injecting new nodes into an existing DOM as the result of an interaction for an MPA, consider keeping those DOMs as small as possible. This will help reduce the work required during client-side rendering to display that HTML, hopefully helping to keep your website's INP lower.

Consider a streaming service worker architecture

This is an advanced technique—one that may not work easily with every use case—but it's one that can turn your MPA into a website that feels like it's loading instantly when users navigate from one page to the next. You can use a service worker to precache the static parts of your website in CacheStorage while using the ReadableStream API to fetch the rest of a page's HTML from the server.

When you use this technique successfully, you aren't creating HTML on the client, but the instant loading of content partials from the cache will give the impression that your site is loading quickly. Websites using this approach can feel almost like an SPA, but without the downfalls of client-side rendering. It also reduces the amount of HTML you're requesting from the server.

In short, a streaming service worker architecture doesn't replace the browser's built-in navigation logic—it adds to it. For more information on how to achieve this with Workbox, read Faster multipage applications with streams.

Conclusion

How your website receives and renders HTML has an impact on performance. When you rely on the server to send all (or the bulk of) the HTML required for your website to function, you're getting a lot for free: incremental parsing and rendering, and automatic yielding to the main thread to avoid long tasks.

Client-side HTML rendering introduces a number of potential performance issues that can be avoidable in many cases. Due to each individual website's requirements, however, it's not entirely avoidable 100% of the time. To mitigate the potential long tasks that can result from excessive client-site rendering, make sure you're sending as much of your website's HTML from the server whenever possible, keep your DOM sizes as small as possible for HTML that must be rendered on the client, and consider alternative architectures to speed the delivery of HTML to the client while also taking advantage of the incremental parsing and rendering the browser provides for HTML loaded from the server.

If you can get your website's client-side rendering to be as minimal as possible, you'll improve not just your website's INP, but other metrics such as LCP, TBT, and possibly even your TTFB in some cases.

Hero image from Unsplash, by Maik Jonietz.